Thimbles, buckets and taps

I’ve been wittering on delivering cogent analysis lately about the importance of productive capacity in the Pacific islands. Productive capacity is defined by some economists as the resources, entrepreneurial capabilities and production linkages which together determine the ability of a country to produce goods and services and enable it to grow and develop.

In other quarters, in contrast, it’s generally imagined that trade agreements will somehow automatically solve all the Pacific’s trade problems; that somehow, given unlimited access to overseas markets, the Pacific island economies will independently generate the corresponding supply. That’s unlikely.

To boost productive capacity countries need an activist government (and maybe even donor community) capable of stimulating capital accumulation, technological progress and structural change through policy. These things won’t happen by themselves. Some of the now-uncool economists like Hirschman and Kalecki said these things long ago.

As I said in this p ost, putting all your faith in market access is a bit like filling a bathtub with a thimble. Better to use a bucket instead, or even turn on the taps — ie. put at least some effort into also developing the domestic economic engine so that there’s enough to export.

ost, putting all your faith in market access is a bit like filling a bathtub with a thimble. Better to use a bucket instead, or even turn on the taps — ie. put at least some effort into also developing the domestic economic engine so that there’s enough to export.

This isn’t true only of the Pacific. My trade diagnostic work in other least developed countries has led me to the conclusion that in most small, peripheral developing countries much more needs to be done to develop productive capacity. Few least-developed economies have the economic flexibility or adaptability to be able to generate much new supply in response to enhanced market access.

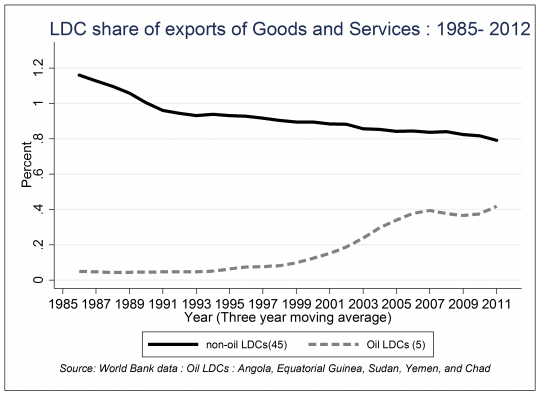

Whatever’s been going on until now hasn’t been working. As this World Bank blog points out:

The world’s 45 Least Developed Countries that are not oil producers (non-oil LDCs) are exporting less and less in the global market place. Between 1985 and 2012, the world market share of non-oil LDCs’ exports of goods and services fell from 1.2 percent to 0.8 percent—all while their share in world population rose from 7.5 percent to 9.9 percent.

These 45 countries — around a quarter of the world’s total, containing one in ten people — have been increasingly marginalised despite their products facing no quotas or taxes in any major market: Australia, New Zealand, China, the US or Europe.

In my view the LDCs are borrowing an inappropriate trade model from elsewhere and need a much more development-focused strategy tailored to their own ends. Good intentions exist in that direction, but with little impact so far. It’s no good imagining that the LDCs can emulate the rich economies and concentrate solely on opening markets (in any case there’s not much more to open) because they haven’t got much to sell in those markets.

European, Chinese and US firms are logically concerned with breaking down overseas trade barriers (although even for them the gains are looking more and more slim). LDC economies are incalculably less complex or sophisticated than these bigger economies and just can’t supply the diversity of goods and services. They face a completely a different scenario.

It’s useful that the LDCs have such huge potential market access, and building domestic capacity doesn’t exclude the possibility of maintaining good access to overseas markets. Nor does it necessarily mean protection (which is another story and which might not be possible anyway). Trade liberalisation also helps countries import more cheaply, which can contribute to economic growth and maybe exports. The point is that to export more, you need to be able to produce more.

Perhaps the Australian government’s recently announced Aid-for-Trade increase could be directed toward developing ‘supply side capacity’ instead of waste-of-time-and-money trade agreements? Innovative, unique and additional support to develop trade opportunities in small island states is a small price to pay if wealthy states are to bolster the legitimacy of the multilateral trade regime. For discussion see: Morgan W. 2014. ‘Trade negotiations and regional economic integration in the Pacific Islands Forum’, Asia and the Pacific Policy Studies. Australian National University, Canberra. http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/enhanced/doi/10.1002/app5.34

Hi Wes, thanks. Yes, maybe the AfT increase should aim at developing productive capacity. I know what you mean but I’m sceptical of the term ‘supply-side’ though, as it has a specific meaning — supply-siders imagine that economic growth is all about competition, deregulation, low taxes, low wages and market ‘efficiency’. Supply-siders are actually sometimes from the same school that says countries should pursue trade agreements.

As we know competition ain’t going to happen in many sectors of economy of a couple of a few hundred thousand people. These countries need more regulation, not less, and in many cases the tax burden is already pretty minimal and/or regressive.

The tradition i’m talking about is more concerned in the domestic economy with the demand side than the supply side. Economists like Kalecki and Hirschman recognised that developing economies were different to developed ones, that they can operate permanently below full demand until something is done to boost production and demand. Getting people into work is one of the most important things.

Also might be of interest: http://www.radioaustralia.net.au/international/radio/program/pacific-beat/surprising-results-from-the-biggest-ever-pacific-exporter-survey/1350238

may also be of interest: Pacific Island Countries: In Search of a trade strategy.

Click to access wp14158.pdf

Cheers. Coincidentally I read this yesterday. Bit of a different story to usual from the IMF. Not enough on productive capacity, not enough on potential comparative advantage in services other than tourism, insufficient treatment in general of linkages as a concept. Otherwise interesting!