Here’s a great presentation of the Just Banking conference held in Edinburgh last April on how to sort out the banks. I particularly like the links between the problems with the credit system and the need to move to a more sustainable, less growth-orientated economy.

Raw materials exports from Africa

Via Unlearning Economics. Africa is still a place where the industrialised countries go to get their resources. Plus ça change.

Bypass the bankers

Ooh, a banking enquiry. Bob Diamond’s geezers will be quaking in their Guccis.

Any proposals aimed at taming the banks won’t amount to much. Better oversight? The financiers will steal all the good staff and run rings round the regulators. Improved central banking? Short of taking the Bank of England back under government control, little will change.

People like Martin Wolf of the Financial Times have suggested measures like prohibiting leverage of more than 10 to one and protecting the vulnerable from predatory mortgage sellers. Separating investment banking from ordinary deposit-taking and lending is critical to stop the bankers gambling with our money.

Those would be sensible ideas, but bankers would probably find a way round them.

Much of the problem is that banks have become so powerful that they run politics. The Tory party is funded by the banks. At least three Tory donors directly profited from the Libor scandal, according to the Telegraph. Labour hardly turn up their snouts at a few quid from the square mile.

As Wolf says: “Protecting democratic politics from plutocracy is among the biggest challenge to the health of democracies.” Financiers have always had their claws in politics — we’re talking the biggest lobbyists in history here — and they’ll push politicians to change legislation in their own favour. That’s unlikely to change soon, and it’s why the Tories aren’t making the banking inquiry independent.

Here’s a development that might really make a difference.

Andy Haldane, executive director of financial stability at the Bank of England, recently said that new technology could make “banking middle men … surplus links in the chain”.

The Internet is great at disintermediating between seller and buyer, cutting out the middleman and creating new efficiencies. Look at the success of Ebay.

The web also cuts costs. Email, Skype, Flickr, Facebook and WordPress. They’re all free because they’ve slashed fixed costs and made it almost costless to produce an additional unit. Why should banking be any different?

Banks also bundle lots of functions and services together. While that may have made sense a century ago, it probably doesn’t today except as a means for the banks to rip us off.

Powered by the Internet, a host of online companies are doing finance in a new way.

Zopa cuts out the high street by taking deposits direct over the Internet and lending them on. Loans are parcelled into small amounts so that any single lender bears only a small part of the risk. Borrowers and lenders decide on an appropriate interest rate and loan length. Zopa now represents nearly 1.5% of the UK lending market with monthly lending of £10-15 million. Only 0.7% of loans go bad, among the lowest of any institution in the UK.

A US website called Movenbank is introducing cashless, teller-free digital banking. Founder Brett King claims that the Internet, like in so many other industries, is revolutionising the business through cutting out the banks.

Kenya’s M-Pesa leads the way in mobile banking. I remember seeing people who’d probably never had a bank account buying food in the Nairobi markets with their mobile phones.

Haldane told the Telegraph that: “At present, these companies are tiny, but so, a decade and a half ago, was Google.”

The magnificence of the Internet is that rather than trying to storm the citadel, it lets the disempowered simply walk round it into new territory. Like many of the best confrontations with power, the solution is to subvert it rather than to wage a war you can’t win.

Caveats

It would be wonderful if the web dethroned Barclays and co., but power always comes into the equation. Online banking might be efficient but efficiencies don’t always pass through to you and me. Bankers have often made arguments on the grounds of efficiency, but usually they appropriate the gains. The financiers will do their utmost to stop themselves being sidelined. Nothing’s stopping them buying Zopa et al. when they get too successful.

A famous bearded German once said that history repeats itself, first time as tragedy and second time as farce. The parallels between the current crisis, 1929, and the 19th century bubbles are eerie, despite the technological differences. Whether it’s the landed gentry drumming up support for their scams in fake railways, stock brokers convincing the credulous that the market will always rise, or Wall Street concocting derivatives that relieved ordinary people of their homes, financial crashes always seem much the same.

Hyman Minsky pointed out that financial stability creates financial instability almost automatically. Long economic upturns make the economy more and more complex, almost inevitably causing it to collapse as financiers try to outdo each other, chasing profits through ever more dodgy investment schemes until the debt created becomes unsustainble. The system is inherently unstable because markets tend to undermine themselves.

Whether or not we cut out the middle-banker, the pressure will always exist for someone to chase fictitious profits, to consolidate, merge and monopolise. I don’t really buy the old argument that the Internet and associated modern technology is somehow immune from the normal laws of capitalism by being inherently devolved. It’s not. Like all industry, it inevitably ends up in the hands of a few: at the moment, Google, Microsoft, Facebook and Apple.

The origin of money is critical. Banks don’t intermediate between savers and borrowers, a key point made by Keynes and Post-Keynesians like Steve Keen. Banks lend first and ask questions later rather than checking first how much savings they’ve got. To a large extent they create money free from the supposed constraints of savings, unlike what conventional theory says. The money supply isn’t a function of savings — it varies significantly depending on confidence, and the data bear this out in recent years. This said, online banking might finally break open the fiction that savers and borrowers are matched through banks.

What’s peculiar about capitalism is that it often sows the seeds of its own instability, as Marx said. Despite all the protests and tweeting by angry activists, it might be the profit motive that finally hits the bankers where it hurts.

What nations are really worth

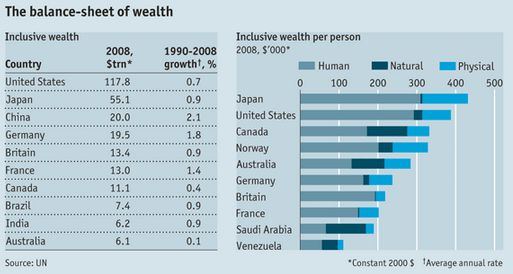

A great article in The Economist highlights a new UN publication on the balance sheets of countries. Gross Domestic Product measures only flows of wealth, not stocks. As the Economist says: “Gauging an economy by its GDP is like judging a company by its quarterly profits, without ever peeking at its balance-sheet.” The new measure, the Inclusive Wealth Index, looks at three sorts of capital: physical (machinery, buildings, infrastructure); human (education and skills); and natural (land, forests, fossil fuels and minerals). China, the United States, South Africa and Brazil have significantly depleted their natural capital bases. Of the 20 countries measured, only Japan maintained its natural capital base, because it planted more forests.

Source: The Economist

The United States still has the largest wealth, at $117.8 trillion, which is 10 times its GDP in the same year (using 2000 prices). US wealth per person, however, was lower than Japan’s. On a per capita basis, there are some interesting differences to the comparable GDP measure, with big, natural and human resource-rich nations like Canada, Norway and Australia ranking third to fifth. High natural resource wealth also sees Saudi Arabia and Venezuela make the top ten.

The list covers only 20 countries, and I suspect that there wouldn’t be enough data to cover many more — which is a problem in itself. But it’s a useful initiative in that it moves beyond GDP, a simplistic and incomplete measure which ignores things like the externalities associated with pollution, or happiness and life satisfaction. It also draws attention away from the relentless growth associated with GDP, which is a problem increasingly recognised not just by environmentalists but by economists.

I’m less convinced the implication that everything has a price. As the Economist points out, the exercise makes all three kinds of capital comparable and commensurable, implying that they are substitutable. The Economist points to the example of Saudi Arabia, which used up $37 billion of its fossil fuels in the 18 years until 2008, increasing its stock of human capital by nearly $1 trillion in the form of school-leavers and university graduates. Surely this sort of accounting game is a bit simplistic?

On the other hand, in rich countries declining marginal returns to investments in human capital suggest that governments should invest in natural capital instead, “restocking their forests rather than their libraries.”

At the risk of drastic over-simplification, Adam Smith can be seen to have revolutionised economics with his notion that the wealth of nations lay not in the gold stocks held by banks but in the interaction of firms and people. Maybe the next step is a measure of wealth that moves away from the relentless accumulation of material things at the risk of deteriorating life satisfaction and physical environment, toward a more sustainable gauge of wealth? Lots of attempts have already been made, like the Human Development Index, the New Economics Foundation’s Happy Planet Index, or Bhutan’s Gross National Happiness Index, but i’m not sure the exact answers have yet been hit upon. As the author of the current report, Partha Dasgupta, says: “An increase in total wealth does not necessarily indicate that future generations may consume at the same level as the present one; as population grows, each form of capital is more thinly spread over the society.”

———-

Update: Having re-read the final quote i’m not so sure I agree with it as it sounds a bit Malthusian.

What economists think about knowledge

I don’t normally bother with other people’s blogposts when they’re so far removed from my own worldview that there’s limited benefit from any engagement. The blogosphere isn’t a marketplace of ideas — it’s an arena for pushing our own pet thoughts, and i’m not conceited enough to think that i’ll change many other people’s minds. But as it happened just as I was writing about economics and its view of knowledge a doctoral candidate at American University called Daniel Kuehn wrote a short piece about why economists shouldn’t do epistemology, which is the study of knowledge. He thinks it’s circular and therefore pointless because it is knowledge about knowledge.

How would one know if one’s got it? How can you even go about getting it if you don’t know what knowledge is in the first place? How would you know about the quality of your knowledge of knowledge? Epistemology is an awfully silly endeavor, if you think about it.

As the first commenter points out, lots of philosophers think about our relationship to knowledge: Plato, Descartes, Kant, Popper, whoever. The term epistemology originated in the early 19th century with a Scottish philosopher called James Frederick Ferrier.

Kuehn, however, thinks they were wasting their time. I wrote on his blog: “In economics it’s certainly acceptable to do epistemology — a non-circular definition might be “thinking about knowledge”. In fact I think that much more epistemological discussion should take place. Why? So much of what passes for economic knowledge has turned out to be questionable, largely as a result of the global economic crisis. Many economists are beginning to understand the difficulties with the knowledge that the mainstream of the discipline has produced (the prominent economists who’ve partially or fully recanted include Stiglitz, Krugman, DeLong, Wolf, Buiter, etc. etc.) It seems sensible to do things like thinking about how we achieved our knowledge and how to make the process of knowledge-generation better in future. This is part of healthy scientific endeavour. We should do much more methodology, too.”

Kuehn replies:

This is fine as far as it goes, but as I’ve noted to other people this sort of thing isn’t really getting into epistemology at all. This is economists thinking a little harder than they did before about methodology. And that’s fine. But there is no new foundational knowledge to ground our claims as true knowledge from any of this soul searching. Nobody in economics or any other science is ever in pursuit of this foundational truth. Nobody cares about that, and the absence of a foundational proposition or “basic belief” hasn’t seemed to do science all that much harm, and that’s my point. It’s not clear there is one. It’s not clear we could know it if there was one. It’s not clear we’d know we had it if there was one and we had it.

If we’re not grounding knowledge in these “basic beliefs” – if our talk is in this way untethered (and we’re not concerned with doing anything about it), then what this untethered talk really is is methodology. And that’s a fine thing to talk about.

The passage is worth quoting because his discussion is self-contradictory. It is epistemology. He’s talking about the possibility or otherwise of knowing about knowledge.

He seems to be under the mistaken impression that epistemology is conducted so as to establish more secure foundations of economic knowledge. That’s overcomplicating matters. It’s just a case of standing back and making observations about what knowledge is, how we can get it and how much can be known about a particular thing.

It’s also weird to suggest that: “Nobody in economics or any other science is ever in pursuit of this foundational truth.” Yes, they profoundly are. In philosophy there’s even a term known as foundationalism, which is the idea that the world is has an independent underlying character which has nothing to do with our conception of it. It holds that science is constructed on logic and sense experience.

Scientists, including many economists, of course routinely make statements about what the world is like, and they’re pretty confident — albeit maybe with a chink of provisionality — about their findings, not to mention their methods. Volcanoes erupt magma. Chlorophyll is a green pigment. Economists usually say things like all other things being equal, a higher price will lead to an increase in supply (although i’d say that sort of statement is much less certain than the other two). A typical view of macroeconomics comes at the beginning of my undergraduate textbook by Greg Mankiw: “Macroeconomists are the scientists who try to explain the workings of the macroeconomy as a whole… as you will see, we do know quite a lot about how the economy works.”

Kuehn’s view is only even worth bothering with because it’s typical of the way economists tend to think about their discipline, which is as a reasonably coherent system that has come close to a true assessment of what the world’s actually like and is gradually accruing new discoveries. They don’t seem to think there’s much need to think deeply about how to do economics or the way it conceives of its own forms of knowledge because they imagine things are broadly on the right track. This view probably originated in written form with Irving Fisher. Fisher’s view, endorsed by Bank of England governor Mervyn King, is that: “students of the social sciences, especially sociology and economics, have spent too much time in discussing what they call methodology.” More recently Frank Hahn said that economists should “give no thought at all to ‘methodology'” (before himself giving lots of thought to methodology). I remember a professor in my department, upon learning that I was studying economic methodology, suggesting that it wasn’t worthwhile and that methodologists should pay rather than be funded for the privilege of studying their subject, since it’s just a luxury.

Kuehn is unusually open to methodology, which is unusual among economists, but he doesn’t seem to realise that epistemology and methodology are closely linked. You’re probably going to say things about knowledge if you are going to make statements about method.

It would be arrogant to preach to the many thousands of accomplished economists about what they should be doing. But as I mentioned above, profound questions arose preceding, during and after the global economic crisis about the things that economics professes to know about the economy and the way that it sets about achieving that knowledge. Few mainstream economists saw the crisis coming. Their ways of doing economics couldn’t even really cope with big snafus. Many of the big hitters have begun to rethink some of their most basic views, and new disciplines – behavioural, experimental, neuroeconomics, econophysics – have sprung into existence.

I’m not suggesting that economists should spend all their time in smoky cafes blethering about the nature of reality. They should get on with the job like most scientists do. But economics degrees should involve a bit of methodology or epistemology, unlike now. Economists might at least spend a fraction of their time — especially at the current juncture — reflecting on whether the discipline really is on the right track.

Maybe i’m being harsh on a student who’s yet to learn. But the problem is that many economists don’t learn. It’s awfully silly, if you think about it.

What is macroeconomics good for?

Paul Krugman comments on a blog by Jonathan Portes supporting macroeconomics against criticisms levelled by Diane Coyle. Portes:

Essentially that she is arguing that macroeconomists (and macroeconomics) have so little credibility in general that it is no longer possible for someone like me, or Professor Krugman, to dismiss the arguments of those who disagree with us on the basis of either macroeconomic theory or empirical evidence; and that therefore macroeconomics has – and deserves – little influence on policy. She contrasts this very sharply with microeconomics, arguing that macroeconomics “does not stand on the same kind of increasingly sound empirical footing.”

Krugman responds to Coyle by saying that in fact the basic findings of macro, particularly the ISLM model, have been borne out by the crisis. But saying that the ISLM model is valid under certain circumstances doesn’t prove that macroeconomics is spectacularly successful. One of the main criticisms of conventional macroeconomics by people like Steve Keen is that it had limited ability to cope with disequilibrium and crisis. Minsky was completely unknown to mainstream economists until his “moment” came, and by then it was too late. Neoclassical economics had little to say about the dynamics of capitalism or indeed about debt — the defining feature of the crisis.

It is this blindness, this wholehearted love of equilibrium, that explains why so few economists saw the crisis coming. Those that did foresee some sort of crisis, like Keen and Anne Pettifor, were completely outside the mainstream.

On the issue of realism of assumptions in microeconomics, we all know that perfect foresight and rationality, etc. aren’t how things work in the real world and that they are used so as to make matters more mathematically tractable. These fictions can be discarded later. But if the central assumptions of a model are so demonstrably untrue empirically, then it’s unlikely they will often get us even remotely close to the truth. If the purpose of the exercise is to flex our mathematical muscles, then it’s not really science, it’s puzzle-solving. Argument and conventional rhetoric can sometimes be better tools. Insisting on the use of unrealistic assumptions just so that you can employ highly formal methods is like using a pneumatic drill to dig a flower bed. The funny thing about Krugman is that he will defend neoclassical economics to the death because his whole career is invested in it and he has won a Nobel prize in it, yet his often sensible policy arguments often don’t have anything to do with neoclasssical economics. They’re the clever thoughts of an insightful thinker.

Don’t forget about private debt

Niall Ferguson is one of those celebrity historians loved by the BBC, a Man With Gravitas who teaches at a well-known university and looks good in chinos on telly. But when he tries to do economics, he’s rubbish.

In the first of his Reith lectures today about institutions and the debt crisis, the Glaswegian claims to have found the “heart of the matter… the way public debt allows the current generation of voters to live at the expense of those as yet too young to vote or as yet unborn.”

He reckons our kids are going to pay for the fast-living of the current generation. It’s an old argument aired by lots of people, like John Kay in the Financial Times a couple of months ago.

Anyone who claims to have identified a single explanation for our economic problems is like one of those bores you meet at the bar who claim that the immigrants are to blame (actually Ferguson comes close to arguing this in one of his books, but that’s another story). It’s all down to the banks/ the NHS/ aliens/ benefits claimants.

There is no heart of the matter. A host of explanations underlie the crisis: the spontaneous tendency of our economic system to build up bubbles; globalisation; the failure of the system of global economic regulation after the war; the unleashing of the financial sector in the 1980s; the abolition of laws designed to separate the investment and retail arms of banks; poor financial supervision; the Iraq war; Blair and Bush dipping into their pockets too much.

But no, Ferguson thinks it’s all about the kids. After arguing that we should probe deeper than just the debate over government debt, which he thinks has led to a pointless battle between austerity and stimulus, he focuses almost exclusively on government debt, completely overlooking the private sector as if only spending on education and health is responsible for the national overdraft.

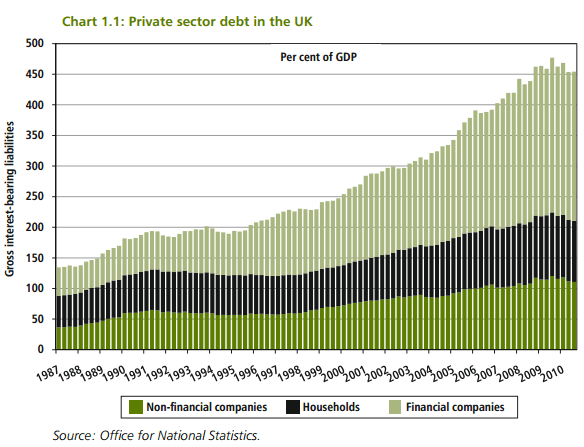

All the evidence shows that in recent decades companies splurged more unsustainably than the government did, and that the private sector bears at least as much responsibility for the crisis. Private sector debt is now about 450 per cent of Gross Domestic Product, four times public debt even on the most pessimistic measure.

Financial sector debt ballooned much faster than government, personal or non-financial debt, and is now higher than all three. By the time the crisis hit the UK financial system had become the most highly leveraged of any major economy, and it remains so.

Ferguson ignores the links between private and public debt. Much of that onslaught of financial-sector borrowing (the light green bar on the graph) was gambling on dodgy derivatives and dubious mergers. When the British government bailed out the banks it socialised the cock-ups made by Fred Goodwin et al. In other words, we all paid.

Public and private borrowing can’t be analysed entirely separately. It’s like pouring water into a glass already part-full: the new liquid is inseparable from the old. The state implicitly acts as a guarantor for companies deemed too big to fail. When public borrowing falls, companies tend to step up their investment, and vice versa. So when Goodwin homes in so unerringly on the government, he’s hit the wrong target. National debt has to be seen in aggregate.

In another outburst of unoriginality Ferguson claims to have identified a new fear for the world’s public finances in coming years: welfare payments and health spending! Wow, I’ve never heard that one before. In the UK, the bank bailout in one blow cost approximately eight years’ worth of NHS funding. A great way of ensuring a poor future for our kids would be to continue allowing free rein to the financial sector.

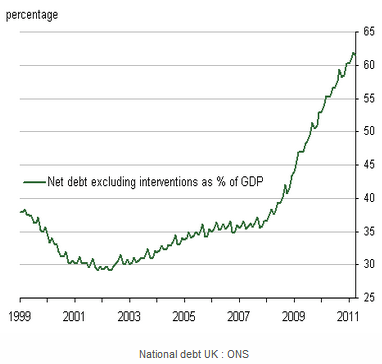

Even Ferguson’s statistics are selective. He quotes the International Monetary Fund, which of course estimates public borrowing to be in a worse state than Whitehall does, at 88 per cent of GDP. According to the UK government, net British debt excluding the temporary effects of the bank bailouts is 66 per cent of GDP. (Include the cash forked out to help our financial friends and the figure is 148 per cent of GDP, although the taxpayer will hopefully earn a lot of that money back when the banks are sold.)

In the end Ferguson plumps spectacularly for a particular side of the debate which he professes to have found so pointless. He thinks not only that we should cut welfare payments but that we should legally limit deficits, publish government liabilities versus assets, and prepare accounts showing what future generations will pay.

In other words, more austerity and more pressure on the poor, just at a time when the economic downturn is so severe that an absence of growth is hammering tax revenues and raising poverty. The following graph shows that government debt, although already rising, spiralled higher after the crisis in late 2007 as the economy slowed and tax revenues fell. The downturn in growth contributed to the debt more than spending did. If we want to look after our kids’ futures, we should restore growth first in order to tackle the debt.

It’s not that public debt isn’t a problem or that we should foist unnecessary borrowings upon our children. It’s that Ferguson’s analysis is about as balanced as a North Korean political broadcast — a situation which is all the more sad given that the BBC endows him with authority.

Lord Reith thought that broadcasting should be a public service which enriches the intellectual and cultural life of the nation. The first Reith lecturer Bertrand Russell, and more recently philosopher Michael Sandel and Aung San Suu Kyi probably did “advance public understanding and debate about significant issues of contemporary interest”. So far, Ferguson hasn’t.

——————————————————

Update:

It’s not just me that thinks Ferguson is a rubbish economist. Jonathan Portes, Director of the National Institute of Economic and Social Research, tweeted “Ferguson not credible on economics. Analysis incoherent.” That follows his earlier link to an article by Ferguson published in the FT in 2009, which I remember, and in which he claims to have won a debate with Paul Krugman, arguing that “this is a big recession, comparable in scale with 1973-1975” rather than the 1930s. After three years of stagnation that view now looks silly, with most serious commentators accepting that a repeat of the great depression is worryingly possible. Britain’s economy basically hasn’t grown at all since that statement was made.

The chino-clad historian continues: “Monetary expansion in the US, where M2 is growing at an annual rate of 9 per cent, well above its post-1960 average, seems likely to lead to inflation if not this year, then next.” Er, it didn’t. Inflation is falling.

“In the absence of credible commitments to end the chronic US structural deficit, there will be further upward pressure on interest rates.” Nope. Wrong there too. Interest rates remain at rock-bottom because of worries about the growth outlook.

His inaccuracy isn’t just a fluke. Krugman was right in almost everything he said, partly because, for all his faults, he at least has a reasonably coherent analytical framework. Ferguson is just a pop-dismalist seizing on current events to grab attention. We should ignore him.

Horses for courses

I have long thought that the small, peripheralised economies in which I do most of my work require a specific approach, one that isn’t provided by conventional economics. The economic world is so varied that it is difficult to analyse almost anything from a pre-defined blueprint. First principles are of course possible, but they shouldn’t involve a methodology so specific as to be only capable of producing a narrow range of results. This is what happened under the Washington Consensus. The man who coined the phrase, John Williamson, in 1989 drew up a list of 10 policies which he thought that most countries should follow: cutting budget deficits and lowering public expenditure; lowering taxes; liberalising financial markets and the exchange rate; reducing import tariffs; abolishing barriers to foreign direct investment; privatisation; and fostering competition. In most places it didn’t work.

This may not just be a matter of whether you are Keynesian or neoclassical. It just might not be possible, for example, to model Brazilian and Tuvaluan trade in remotely the same way. The sort of economics required to study the US stock market is far removed from the kind needed for looking at the communal, subsistence societies of many poor, rural communities in the developing world. One is individuated, atomised and behaves according to certain well-analysed patterns of behaviour which can be readily mathematised (although in light of recent events many rightly question the success of financial economics), the other is communal, possibly less predictable and less quantifiable, and the goals are altogether different. It’s not good enough just to use different models and techniques (which happens already). I wonder whether economics should come up with entirely separate modes of analysis for a range of different country categories, modifying these categories based on evidence and results. My external PhD examiner Geoff Harcourt, for example, a prominent post-Keynesian, advocated something like this, terming his methodological approach ‘horses for courses’.

Economics in small island developing states

The following example, from small island developing states (SIDS), is based on a paper i’ve worked on with Dan Hetherington. The unique character of SIDS poses challenges to standard economic theory, and the failure of policy initiatives that have failed to take this into account is a common feature of SIDS’ experience. Contrary to the assumptions of traditional economic models SIDS never experience perfect competition or even a close approximation of it; they face severe uncertainty; and in several SIDS, particularly in the more community-orientated cultures of the less-developed SIDS, individualistic utility maximisation is an inappropriate framework within which to conceptualise economic activity.

In trade, one of the most promising avenues of development for SIDS, a conventional neoclassical economic approach is often applied irrespective of the size, fragmentation, distance and vulnerabilities of SIDS. Standard economic theory predicts that a country will tend to specialise in its comparative advantage, and that opening up by liberalising barriers to trade will help generate a more efficient productive structure, with a country exporting products and services at which it is more suited to producing and importing goods and services at which trading partners are better at producing. Countries are supposed to specialise in the products for which the relevant factor – labour or capital – is relatively abundant. It tends to be assumed that the supply response is automatic. The standard neoclassical method has promoted a tendency to focus on the demand-side rather than the supply-side, and to reducing trade barriers through trade agreements and domestic liberalisation rather than to building productive capacity through state or donor intervention.

As an approach to development this theory is not particularly helpful in many SIDS. (Some question whether the approach is relevant anywhere, including Keen (2011), Rodrik (2008), Stiglitz and Charlton (2004, 2005), and Chang (2007)). Many SIDS are so small and undeveloped that the range of options for production is limited and competition is highly imperfect. In several of the 65 inhabited islands in the Vanuatu archipelago, for instance, there is limited infrastructure, including no asphalt roads, no wharves, limited electricity and highly infrequent inter-island transport. Participation in the cash economy for some islands, often with a only a few hundred inhabitants, is limited to cutting copra and selling it on the beach when a ship happens to visit. It is unrealistic to expect new infrastructure and in turn economic activities to emerge soon without significant external intervention. Long-term specialisation in copra production, one of the lowest-valued international commodities, is not conducive to development. Moreover the production base is so small that the development of goods exports is curtailed and the majority of consumer goods must be imported. Most Pacific island states have run persistent goods trade deficits since independence. World Bank data shows that goods trade weighted by GDP is 60% of total trade for SIDS, compared with 80% for low income countries.

The relative abundance of labour or capital becomes something of a secondary question owing to factor immobility and a lack of technology, skills or training. Again, in Vanuatu, which attracts considerable foreign capital as a tax haven and which for an officially least developed country has a relatively high GDP per capita of $3,042, the vast majority of economic activity and investment is concentrated in the main island, Efate, an outcome which is concomitant with the extreme inequality between the main towns and elsewhere. Capital does not move easily to different geographical locations. Cultural and linguistic barriers present a surprising barrier to labour mobility between and among the outer islands, and educational attainment must improve further before a rapid move is made into value-adding activities.

Winters and Martins (2004) confirm this generally critical view of conventional theory by quantitatively examining the higher costs faced by SIDS, which leads them to argue that the combination of transaction costs and scale diseconomies alone may prevent SIDS from participating in the world economy without preferences, concluding that “free trade could mean no trade for these economies.”

This is not to suggest that the development of trade is not possible but that the standard approach to trade is misplaced and that a greater role for external intervention is both necessary and inevitable. Markets are frequently highly undeveloped or non-existent, and either they must be actively stimulated by some kind of external agency or some economic activities must be conducted by the state. Moreover governments and development partners have focused unduly until now on goods rather than services trade.

Government in SIDS

One specific economic challenge facing SIDS is a unique role for government owing to the significance of natural monopolies. In some cases even corner shops can form a natural monopoly on a sparsely populated outer island. Kiribati, Tuvalu, the Solomon Islands and several other SIDS have distant islands with only a few hundred inhabitants, restricting competition and the functioning of markets. Government must play a ‘backstopping’ role, making its size and remit larger. In many cases more consideration needs to be given to the role of the state as a complementary or supportive player in the development process.

Some government functions are indivisible, and these constraints can be inevitable and permanent. For instance several countries do not have the resources to devote sufficient time and attention to trade negotiations. Outsourcing certain government roles has been considered.

An further important reason why the state plays a particular role and why SIDS deserve special attention is that they are more vulnerable than other developing countries. UNCTAD research finds that they are a third more vulnerable to external shocks with economic consequences than other developing countries. SIDS are 12 times more exposed to oil price-related shocks than non-SIDS and structurally at least 8% more vulnerable to climate change effects than developing nations in general.

Again, all these specificities are more than just deviations from a methodology which remains basically right in most respects. They are fundamental departures from the mainstream of economics, and require a fresh approach to thinking about economics in this context. I’ve always thought that the defence of unrealistic modelling by people like Paul Krugman was faintly ridiculous: we use unrealistic assumptions like rationality and perfect foresight so as to be able to do modelling, and later relax those assumptions during the application of models. But if you’re journeying to London, why start from Inverness when you can start from Oxford?

References

Chang, H-J. 2007, Bad Samaritans, London: Random House

Keen, S. (2011) Debunking Economics, London: Zed Books

Rodrik, Dani, 2008 One Economics, Many Recipes, Princeton University Press

Stiglitz, Joseph and Andrew Charlton, 2004, “A Development Round of Trade Negotiations?”, paper presented to Annual World Bank Conference on Development Economics: Europe, Brussels, 11th May 2004

Stiglitz, Joseph and Andrew Charlton, 2005, “Fair Trade for All: How Trade Can Promote Development”, Oxford: Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-921998-8

Winters, Alan and Pedro Martins, 2004, “When Comparative Advantage Is Not Enough: Business Costs in Small Remote Economies”, World Trade Review, 3:3, pp347–383

#Greek #euro exit may not be so horrifying

Gideon Rachman says that Greece should leave the euro. He’s probably right, because the currency was badly-designed from the start. Investors were never likely to shift funds quickly to economic black spots. Workers wouldn’t move to areas with lots of jobs on offer because they couldn’t speak the language and they wouldn’t fit in with the culture.

To compensate for the resulting inequalities, the eurozone had no central authority that could redistribute funds. The strictures on government spending were so anal that not much could be done to stimulate demand or help the unemployed — but in any case the lack of law-enforcement meant that most governments periodically thumbed their noses at the rules. As I noted in this post, a paper by the Graduate Institute in Geneva found that France breached the spending limits in seven of the 12 years after the euro began and Germany five.

A low interest rate that helped the sluggish north was never going to suit the more volatile economies of Greece, Portugal, Ireland or Spain. Cheap money helped inflate housing bubbles and allowed governments to escape the need for proper tax systems.

In a kind of collective neoliberal wish-in, the eurocrats hoped blindly that their scheme would somehow work. They blame the Greeks, but it was always going to be one of the poorer fringe countries that would come off worst. The Germans and French like to forget their own misdemeanours.

Because the euro is so flawed in so many ways, it almost certainly can’t continue in its current form. Rachman’s probably right to call for an ordered break-up rather than a messy balls-up. “Better an end with horror, than a horror without end.”

I’m not convinced, though, about the extent of the horror. The FT writer says that:

the exit of Greece would unleash contagion, by making it clear that membership of the euro need not be permanent. Markets would inevitably round on the next vulnerable countries.

Yes, an unplanned exist would be disastrous, and one of the only predictable outcomes is higher borrowing costs for the remaining eurozone. But surely everyone can already see that membership isn’t permanent? In that mangling of language so beloved of financiers, pundits have been worrying for weeks about the ‘Grexit’.

Markets are already rounding on the vulnerable. Bond yields periodically surge to levels that can only be associated with a euro break-up. Hundreds of billions have already been whisked from Greece and Spain. Greek shares are lower than in 22 years, while the Spanish stock market is at its lowest level in nine years.

And as Rachman points out, the long-term costs of sticking with the euro for Greece, and maybe others, may outweigh the temporary catastrophe that accompanies exit. In a country like Spain, every week with the euro is another week of misery for the quarter of adults who have no job. It’s more erosion of skills, one more young person’s potential squashed.

Germany and France could inflict as much austerity as they wanted in a smaller core eurozone — and they wouldn’t have to worry about bailing out the periphery. What the core eurozone leaders and bankers are really scared about when they talk of contagion is losing the money they’ve lent and having to pay a higher interest rate on their debt. They’d no longer benefit from the free money that’s washed around the continent for the last couple of decades.

Meanwhile a devalued south could default on its debts and work on restoring growth and building exports. Other recent defaulters and devaluers — Indonesia, Argentina, Russia — have rebounded quickly after crisis. Better to get the pain over with quickly than to inflict death by a thousand cuts, and better to think first of the poor rather than the bankers who got us into the mess in the first place.