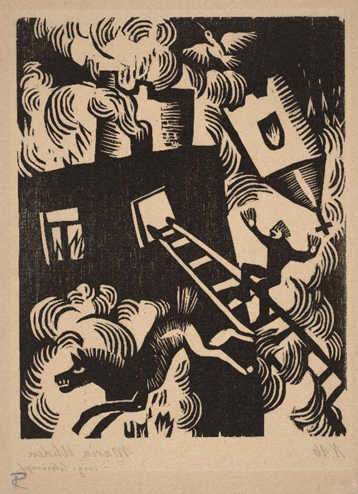

The burning of the old order

A true story

A young man sits on a red couch in the lobby of Jakarta’s Marriott hotel, having just walked from his cheap digs round the corner. He’s hot and jaded after a night drinking Bir Bintang. Beige chinos and a blue cotton shirt that sticks to his back are the livery of an eager western journalist in the tropics.

A waitress pushes a trolley past wearing a white uniform, starched, like a nurse’s. He orders a glass of water and a coffee. Milk, no sugar. Muzak burbles from somewhere unknown. Simply Red or Michael Bublé? He doesn’t care; he’s more into techno. His mind is already drifting back to the impressionist blur of the bar at Tanamur and the taxi ride home.

He’s here to interview a renowned Professor of economics from Princeton University, who’s flown in a day late after getting the time zone wrong. The young man rereads the half dozen questions he’s scribbled in blue ink on an A4 sheet.

The list seems banal and makes him sound stupid. His interviewee might sneer. Will an American academic have any idea how fast the region’s economies will grow this year, the first of the new millennium? Surely he’ll pierce through the young reporter’s feigned insight.

Most of the questions are cribbed from the web. Are the World Bank and International Monetary Fund bad? Will East Asia’s lingering debts slow progress?

The young man had arrived in the region a couple of years earlier, when burning Sumatra blew smoke across the Straits of Malacca. A brown veil covered the window of his forty-second-floor office. Outside, his lungs hurt. Locals wore masks decades before they caught on in the rest of the world.

The haze, as locals called it, was caused by Indonesian farmers slashing and torching forests to plant new crops. It enveloped whole countries, seeming to mark the end of the economic boom, a time when countries leapt from the shadows.

Sometimes the haze clouded the young man’s mind.

He fidgets. He’s read the Prof’s best-seller (only later realising it was a play on the title of an 80s novel and film) and tried in vain to understand some of his academic papers. A decade earlier the Prof had won a big medal for up-and-coming economists – often a pointer to the Nobel. Like most liberals of the time, the young man hoovers up the Prof’s blogs and journalism.

As the young man shifts again in his chair an average-sized bearded man with curly dark brown hair ambles across the hotel lobby. He wears an open-necked checked shirt and a blazer. He smiles modestly.

The timid inquisitor shakes the hand of his jetlagged respondent.

Pleased to meet you-hope you had a good trip-apologies for lateness-never mind (the young man was secretly glad he could spend another evening in the bar).

“Do you think Malaysia’s capital controls were a good idea,” he blurts.

The Prof makes a sound like a surfacing whale. “Oh, not that old line again.”

“If you ask me, it was too late.”

The Prof patiently explains what capital controls are: a ban on foreigners trading Malaysia’s currency and limits or levies on how much they can bring in and out of the country.

He says tax might sound like a good way for Malaysia to stop investors from fleeing, but the worst has already passed and the rest of the region’s economies are beginning to grow again.

The IMF and the World Bank hate the capital controls, he continues, because they violate the free-market rulebook. For that reason, lefties love them.

“Will capital controls scare away foreigners in the future?”

“Probably not, because everyone’s so desperate to make money.”

“How do you see Asia’s – and the world’s – economic prospects now that the crisis has passed?”

The Prof again exhales. He says that one of the main things about the world economy in the last few decades is that the United States buys much more from abroad than it sells – $400 billion more in 1999, to be precise.

Other nations make the trinkets that rapacious US consumers crave. American manufacturing has long been dying, so more goods flow into the States than out. “More and more of our imports come from overseas,” President George Bush said that year with a straight face.

You’d expect this deficit in trade to kill demand for the US dollar, continues the Prof, but the currency stays strong because the world – and particularly newly rich Asian business owners – invest their profits in American housing and shares.

“In accounting terms…

Oof, if ever there was a phrase designed to test the attention of a sleepy interviewer. The young man’s bum suddenly hurts and he shuffles in his seat.

“… by definition if a country spends more than it earns from trade, it has to borrow or attract investment from abroad to make up the difference. The numbers are roughly equal but opposite—one’s a deficit, the other’s a surplus. The US capital account surplus, or excess of savings, is the inverse of the current account deficit.”

How this plays out in practice, continues the Prof, is that the dollar and the explosion in American financial markets feed on Asia’s rise.

Huge, booming nations like China and Indonesia offer oceans of cheap labour and resources. Asia’s upturn, based on cheap wages, act as the flipside of the US trade deficit and strong dollar.

Plus, Washington mints the world’s currency so everyone has to use it.

“Who knows how long this’ll all last? As long as it does, the world’s probably going to be OK,” says the Prof.

“But the dollar’s strength despite the trade deficit is like when the cartoon character Wiley Coyote runs off a cliff into thin air. Sooner or later he looks down and plummets to the ground.”

Later, digesting the Prof’s lesson, the young man takes a taxi to Kota port in the north of the city. The pointed prows of a hundred wooden pinisi sailing ships adorn the quay. From a distance they look like they’re for the tourists.

As he nears, he finds out that the vessels travel onwards to Sumatra carrying wood from Borneo. Painted white with a red stripe, they sport ketch rigs with ratlines running up their masts. Planks down to the quay bear sweating, barefooted men wearing sarongs, each of whom heave six hardwood beams ashore.

The young man wishes he had a better camera to capture the people; and to photo the ships, which look they’re from a Conrad novel. During half an hour at the far end of the dock he watches a dispute between three hulking, barefoot local Indonesians plastered in dust, and an Indonesian Chinese man in a smooth suit who then barks instructions down a mobile phone. The wild, angry stevedores stare down from the truck they just loaded. The slim, immaculate boss refuses to look them in the eye, and chatters.

Many locals blame the economic malaise on the ethnic Chinese, who own a lot of businesses but mostly don’t do the hard graft. Tales circulated of businessmen selling their Mercedes for a few grand at Soekarno-Hatta airport as they fled ethnic unrest.

But it wasn’t about race. The crisis was the result of hubris and the insatiable appetite of global investors for high returns. It was a regional bubble stoked by hot money flowing in from abroad and suddenly out again, fuelled by America’s thirst for stuff and blossoming Asia’s happiness to oblige – cheaply.

Those stevedores are like hundreds of millions of low-waged workers across the region who power the boom. Their bosses plough the profits into the booming US stock and property markets, propping up the dollar, whose strength boosts American buying power. The United States and Asia are the pincers of a huge crab encircling the globe.

The young man walks on toward Jakarta’s LapanganMerdeka, or independence square. Towering within is the Monas monument, known locally as Sukarno’s last erection, after the first president who was kicked out in 1967.

More and more green-uniformed policemen in riot gear carrying four-foot yellow batons. A training exercise, he wonders, in readiness for more demonstrations against the regime?

As he draws closer to Jalan Thamrin he comes across students chanting “save Aceh” in English.

The students, numbering around 200 and from Jakarta’s Muhammadiyah University, wear headbands bearing the slogan “Aksi Peduli Aceh,” or Aceh Solidarity Action. A police battalion skulks awkwardly at a distance, flowers adorning guns. Gudung Garam cigarettes lace the air with cloves.

A powerful woman wearing a green tudong bellows slogans down a megaphone in front of the sitting demonstrators. She punches the air with her fist, inviting the others to follow. The young man thinks his protests against student grant cuts in London were trivial.

Someone gives him an orchid, and a badge with a black ribbon which he ties to his rucksack. He chats with one of the organisers, Irwan, who tells him that the demonstrators are protesting against army oppression in Aceh, the northernmost Sumatran province long ruled by Java but with a long and fierce history of independence.

Irwan says he disagrees with a new proposal that the army should automatically have seats in parliament. “The army chief should step down,” he says.

The police say the protest must end at 4 o’clock. Irwan says they will leave to avoid a confrontation. He doesn’t blame the cops. What’s important is “the system”. He says that what matters is improving democracy and helping workers.

Students like him are the product of Asia’s prosperity. Their education and new freedoms prompt them to question the old regime. It’s only a couple of years since the overthrow of dictator Suharto, and a nation is being rebuilt.

Irwan and his friends will again grace independence square.

A year later the young man retired his blue cotton shirt and beige chinos, returning to university to study more economics. He’d been too shy to hunt down big scoops, and his editors didn’t want him to peer through the haze. They were only interested in what was good for American business.

In Singapore, he wasn’t allowed to touch politics in case the censorious regime kicked his magazine out of the country. The story was all about the city-state’s prowess in science, a sparkling new trade deal and how the buses ran on time: Singapore-lah.

An article he wrote about Aceh had to be about how activists used the Internet rather than why people wanted to break with Jakarta after decades of violent oppression. And anyway in the end it was the sea, not politics, that killed the dream of independence. The Indian ocean Tsunami in 2004 swallowed up some of the Acehnese campaigners he interviewed in the province, along with nearly a quarter of a million other people.

The Prof won his Nobel prize. A quarter of a century later he quit his newspaper column so that he could rail more freely against US president Donald Trump on his blogs. He’d become a kind of thought-haven for right-minded American liberals.

He described the US president variously as a virus infecting American capitalism; a cancer that grew in the dark; and like Mao’s cultural revolution – an attack on democracy and intellectual inquiry.

Wiley Coyote seemed to hang in the air, as the chasm beneath him, the US trade deficit, more than doubled to a trillion dollars. The world kept ploughing money into American shares and property, driving an explosion in wealth and inequality as the pay of US blue-collar workers stagnated while investments in housing and shares rocketed. By 2025 the richest top tenth owned nearly three-quarters of household wealth and about nine-tenths of the stock market.

The profits from work outsourced to Asia were recycled so hard into American assets like houses, that the annual salaries of Gen-Z now bought less than a fifth of a house, compared with half for a Boomer in the 1950s.

The average Gen Z blue-collar worker in the Midwest was now worse off than their grandparents. Pay lay in the gutter. Such generational decline was a first in the country’s young history.

Any doubts about Asia’s economies recovering from the crisis were immediately dispelled as they started racing again, led by China.

There, factories tripled their output in the next decade, outpacing all other major economies. When the young man lived in Asia, China made about 6% of the world’s stuff. By 2025, a third of everything was made there. Add in Asia and the share grew to more than a half. The idea that the region might sputter and fade was, in retrospect, ridiculous.

Those Jakarta stevedores may not have been on the factory floor, but they were part of the often invisible, hard-working and low-paid regional working class that fuelled these emerging nations and supplied the world’s goods.

The wood that built things; the people who carried the wood; the ships that transported them; the coal, oil, copper, and nickel; the factory workers on subsistence wages—they built the new millennium. They had more in common with their rustbelt brethren than they knew.

The global financiers who profited from this feature, and the politicians they funded, would wheedle resources and cheap labour from wherever they could for as long as possible. Americans seemed hard-wired to consume. The US would never return to some golden age of middle-class prosperity where the international trading ledger balanced.

Yet Trump campaigned on the impossible promise to eliminate the trade deficit. In all his idiocy, and without being able to articulate it, he was preying on the anger at the global system; the inequality that arose from wage stagnation and the boom in asset and house prices.

In his dim, animalistic way, the president knew that this global lop-sidedness was the cause of his voters’ problems. His solution – balancing the trade account via tariffs – was blunt and stupid, and he kept changing his mind.

But he and his advisors were in effect responding to the Prof’s lesson from back in the year 2000, that a country has to borrow or attract investment from abroad to make up the difference. To cut the trade deficit, Trump and co now wanted to stem the tide of investment flowing inwards.

Paradoxically it was the United States, not wayward Malaysia, that now proposed controls on capital. Trump in 2025 proposed tightening investment rules, making it harder for supposed adversaries like China to invest in sensitive American sectors like tech and land. He proposed taxing foreign investors whose governments purportedly acted unfairly against the US. Some of Trump’s advisers even floated the idea of charging foreigners to buy US bonds.

So it was paradoxically the US that ended up scrapping the free-market rulebook, not Asia.

The young man came to realise later that the Prof., a savant who mixed metaphors and so hated Trump, missed the point. The cheap Asian labour and resources that fed the global boom, and the American appetite for more goods than it made, weren’t aberrations that debased the economy; they were a feature. It was how the global economy worked. There was no cliff, and no Wiley.

Trump wasn’t a virus, a cancer, or Mao. He was a response to a decades-old feature of the global economy that enriched the rich and trampled the have-nots. Wishing for a return to some mythical normality wouldn’t help. Populists – Trump or otherwise – would keeping stoking the discontent and benefitting from it.

The young man, not so young or eager now, occasionally thinks back to his time in Asia. He’s still into techno and occasionally goes to bars – though less often. He sometimes reluctantly labours under the label of economist, and spends too much of his time thinking, rethinking, and wondering how far the smoke will spread.

If ever a blog would have benefitted from a supporting playlist, it was this one.

all best Jannie

Sent with Proton Mail secure email.

Thanks Jannie – appreciate the analogy. In my dreams it’d be a banging late 90s dancefloor classic like Darude’s Standstorm, but I realise that’s overambitious 😉