Shaky progress: structural transformation in graduating Pacific least developed countries

I’ve just published a new UN working paper on the Pacific’s least developed countries (LDCs). The paper finds that whilst these economies have been growing reasonably quickly, bringing them to the point where they’re eligible to leave the LDC category, their structures aren’t changing fast enough or in the right ways to spark widespread transformation.

The countries in question — Kiribati, Solomon Islands, Tuvalu and Vanuatu* — aren’t industrialising. This might not sound surprising, but the paper shows so clearly, with international data stretching back two decades. The finding has far-reaching implications for the region and similar countries.

In theory, developing economies are supposed to move from low-productivity activities like agriculture to high productivity pursuits such as manufacturing. Factories are important because they build mass employment for subsistence or agricultural workers and increase value-addition. In turn this raises living standards and creates the wealth needed for investment in health and education.

This hasn’t been happening in the Pacific (or in many other LDCs, for that matter). Economic output has shifted away from agriculture over the past 20 years, but mostly toward services. Almost all new jobs created have been in retail and tourism — progress, but shaky.

As we’ve seen in the Covid-19 crisis, tourism is vulnerable to global instability. The industry almost completely screeched to a halt in 2020. Last year’s 74% collapse in global visitor numbers was the biggest ever, according to the World Tourism Organisation. For a country like Vanuatu, the LDC most dependent on tourism, this was devastating, removing the main source of foreign exchange, investment and secondary economic activity.

Most simple services like tourism and shopping are inherently less productive. A tour group, for example, can only reach a certain size – maybe 20-30 people per guide – before it becomes unviable. A shop can only employ so many assistants, and pay is limited. The gains from mechanisation can, in contrast, be extremely high as marginal costs fall.

Not only are the Pacific LDCs failing to industrialise or to raise productivity, but trade liberalization hasn’t produced the desired results either. This runs counter to the mainstream theory, which says that exposing the economy to international competition should encourage entrepreneurs or existing companies to move into areas in which the country has a comparative advantage, in turn improving productivity.

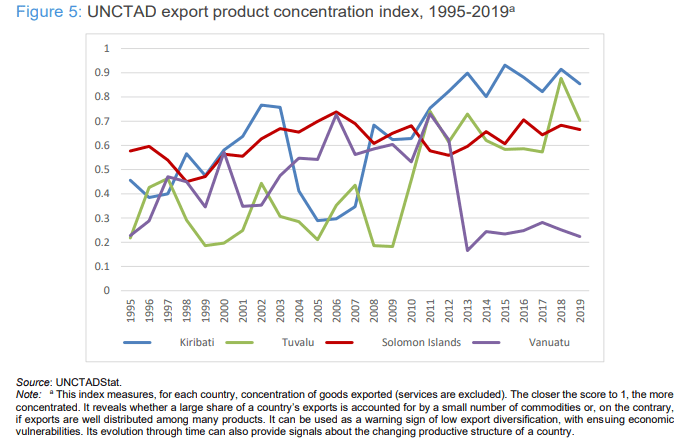

In the Pacific, trade hasn’t grown much relative to the size of the economy. Exports in three of the four regional LDCs have become less diversified since 1995.

It shouldn’t be too much of a shock that the traditional idea of structural transformation doesn’t apply in the Pacific LDCs. These countries are tiny, all falling within the world’s 15-smallest by population. Tuvalu has the smallest economy of any independent territory in the world. GDP is about the same size as the US city of Albequerque, or Edinburgh, Scotland’s capital city. If you added up the GDP of all four Pacific LDCs it’d still be smaller than that of the Central African Republic.

They’re enormous by sea area. Kiribati covers the 12th-largest sea area of any country, 3.4 million square kilometres — bigger than India’s total land and water area, and much bigger than the Caribbean Sea. Because the islands’ small populations are spread across such a wide area the workforce is mostly very fragmented, raising the cost of domestic transport and limiting economies of scale.

These countries are so spread out that their producer and consumer bases are miniscule. Isolation means that trade costs are extremely high, making import and export costly. No Pacific island capital is within 2,000 km of Sydney or Auckland.

Whilst it isn’t a big surprise that the standard theory proves inappropriate, it does raise the question as to why so much international advice and thinking runs along conventional lines. It doesn’t make sense to recommend normal routes to industrialisation, or to continue to spend so much of the region’s extremely scarce human resources on yet more trade negotiations.

Most of the economy in these countries isn’t market-based or commercial. Subsistence still plays a big role in Melanesia and beyond. Domestic economies will never be very flexible because of their peculiar characteristics, so policies that aim to alter incentives or free up markets will only have limited impact.

Dependence on government spending across the four countries is so high that on average it forms 80% of GDP . By comparison the LDC average is 11%. Transfers from abroad, donor aid and remittances are also historically huge. None of these things are affected by national policies aimed at stimulating markets or cutting the role of government.

There’s a need to think creatively about analysis and policies. New, context-sensitive ways of thinking about economic transformation must be conceptualized and enacted to promote the next phase of economic development.

The paper tries to start thinking a bit deeper about what this might mean in the very special circumstances of the Pacific. Part of the challenge lies in escaping the old ways, and not continuing to adopt models drawn from other contexts.

Firstly, governments and donors will remain a large part of the economy for many years to come — in many cases not just as a complement to the private sector or as a source of incentives, but as a source of service provision, resilience and ultimately a component of aggregate demand. Trying to shrink fiscal expenditure in the name of efficiency will often only weaken economic growth.

Secondly, linkages should form a much higher priority than they have done until now. The region could capitalise much more on what is termed the ‘blue economy‘ — leveraging the region’s huge ocean resources sustainably for tourism, fisheries and niche, high-value agriculture. Government and donors can play a role in stimulating production up and down individual value chains so that more money stays inside the country and local producers benefit from tourism.

Thirdly, institutional management should be rethought. Instead of spreading skilled officials across 10 conventional Westminster-style ministries, valued staff should be brought together in a single economic management unit. Some countries, like Singapore and Rwanda, have based their entire development strategy on economic development boards. Consolidation would lead to better coordination in areas like linkages policy.

Fourthly, the so-called fourth industrial revolution isn’t too advanced for the Pacific, and any hope for structural transformation should take into account modern technologies and the increased merging of manufacturing and services. Whilst many developing countries fear the loss of jobs to robots, this isn’t a concern for a region that never industrialised. At a stretch it’s possible to imagine the region leapfrogging some previous technologies.

Major opportunities exist in services with low start-up costs where physical location is less important and which serve the international market. Business process outsourcing and microwork may have potential. Tourism is now even possible online. In September 2020 Amazon launched a new service called Explore that allows customers to book live, virtual experiences led by local experts who conduct virtual tours.

New processes like additive manufacturing are almost made for the region. In principle 3D printers could make products using recyled raw materials, reducing the need to import things thousands of miles on expensive shipping routes.

Drone and surveillance technologies could benefit fisheries and the environment. For instance a New Zealand company is currently trialling an autonomous sea craft to police Pacific waters. The sea-based drone can detect illegal fishing, help with search and rescue by deploying life rafts; assess cyclone damage to remote islands by launching aerial drones; and collect scientific data, particularly on climate change.

Its energy comes from solar panels and a horizontal wind turbine, which power batteries that enable the craft to operate autonomously for long periods. Such technologies can address many of the challenges faced by island countries simultaneously, including illegal fishing, safety at sea, and climate change.

Technology is no panacea, and the fourth industrial revolution will not provide all the answers for structural transformation. Policies will remain critical. Governments will among other things need to keep tackling the uphill tasks of education and training; rules and regulations; lowering the cost of internet access and speeding it up; and making the living environment attractive enough to retain skilled workers and attract new investors.

Donor partners will need to keep investing in the region, and taking enough of a hands-off approach to allow policymakers to make mistakes and learn from them.

The paper is by no means exhaustive, and plenty more ideas along these lines are needed. Neither does it deny the progress that the likes of Vanuatu has made in tourism. But hopefully it shows that thinking a bit differently and seizing on new trends may yield dividends for the region — as well as small, marginalised countries elsewhere.

Download the paper here (pdf), from the UN Economic and Social Commission for Asia and the Pacific (UNESCAP) Macroeconomic Policy and Financing for Development (MPFD) Working Paper Series.

*Vanuatu graduated from the LDC category in December 2020.